Since its outset in 2014, the war in Yemen has internally displaced some 4.8 million people and left 20 million relying on humanitarian aid, according to UN estimates. Often overshadowed by other conflicts, the impact on civilians now rarely makes international headlines. Even less discussed is the conflict-related sexual violence committed by all parties to the fighting, including both government forces and Houthi fighters.

When GSF began working on the Yemen Global Reparations Study, in 2023, a team of experts met with a small number of survivors across Yemen and Egypt, some of whom wished to meet in secret for security reasons. The research team also met with organisations supporting them. What emerged is a bleak picture of abuse, displacement, and a critical need for survivor-centred support both at home and in the diaspora.

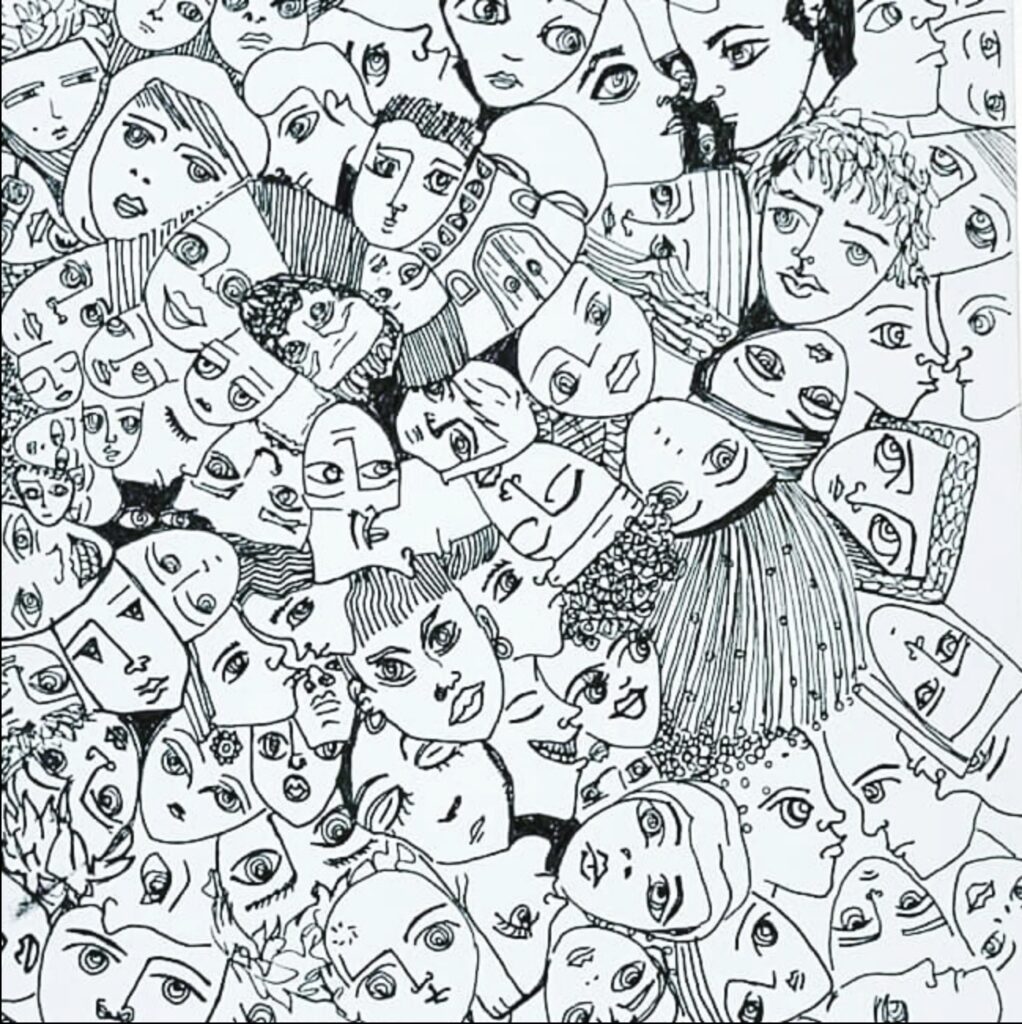

Different facets and faces in one nation. Yemen, July 2025. Najla Alshami

For researcher Nuria Abdel Kader, who lives in the capital Sana’a, displacement is central to understanding sexual violence in Yemen, leaving women and girls in particular with no support system. Over the course of her research, she and her team collected data from camps in six governorates hosting the majority of Yemen’s internally displaced population, including Hodeidah, Aden, Ta’iz, and Ma’arib. Often having fled with nothing, and separated from male relatives who act as protectors in a traditionally patriarchal society, her research found that displaced women and girls are trafficked, forced into marriage and prostitution, and raped.

Ma’arib governorate alone hosts more than 200 camps for internally displaced people (IDPs). Some are located near military bases, putting women and girls in camps at heightened risk of abuse from the military, as well as sexual violence committed inside the camps. Yet both survivors and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) face risks in reporting instances of conflict-related sexual violence, according to the research team. This contributed to the difficulties in directly accessing survivors for contributions to the Study, which was deemed to be a high security risk.

“Both survivors and NGOs working with them are afraid of giving their names,” Nuria said. “They asked to give me information, but anonymously, because they’re scared of local authorities.” As for the survivors themselves, she adds “there is no one to protect them.”

Even when survivors do seek help, support is limited. Options offered by civil society and NGOs operating in the camps has been curtailed by funding cuts and sanctions, leaving victims of sexual and gender-based violence with few resources. The GRS found survivors urgently need psychosocial support, safe shelter, and confidential medical and psychological care, while Nadia outlined the impact of funding gaps.

“We have a lack of health workers, for example, in cases of rape, [some] NGOs we spoke to can’t deal with them – they don’t have any rape kits,” she said.

For displaced Yemenis who live outside formal IDP camps, there is “no support at all,” Nuria adds.

The essence of the community without recognition. Yemen, July 2025. Najla Alsham

‘Honour’ killings and dangers in Egypt

The challenges for survivors extend beyond Yemen’s borders.

Many Yemenis have fled to Egypt, where most now live in Cairo and Giza and eke out precarious survivals. There, survivors described to our researcher Nadia Ebrahim the struggles they face – including poverty and the looming threat of deportation.

Many of these issues are faced by refugee communities worldwide. However, Nadia says, “Sexual violence, including rape and other forms of abuse, that is really part of the conflict that has extended out of Yemen.”

This includes both stigma unfairly attached to survivors, and the very real threat of honour-based violence.

Survivors can be killed “even if they are victims,” Nadia said, noting cases of women and girls who have been traced and attacked in Egypt because of the stigma surrounding sexual violence. Both Nuria and Nadia describe conducting interviews in various locations, including their own homes, to protect the identities of the survivors.

“Even if survivors were raped or just tortured, their families, some of them, reject their sons or daughters – especially the girls,” said Nadia. “Some of them have been killed in the name of ‘honour. Even if they don’t say it directly, sometimes you can tell with their body language, you can read between the lines that they are afraid of the stigma,” she continued.Nadia, a Yemeni refugee herself, spoke with both Egyptian and Yemeni organisations to understand the struggles refugee survivors face. Those who fled Yemen, she says are often unable to work due to visa restrictions, cannot afford to send their children to school, and avoid reporting abuses for fear of imprisonment or forced return to Yemen. Some were abused in detention in Yemen. All of these make them vulnerable to further violence, including forced marriage and trafficking.

“They’ve been severely affected by the war, but at the same time leaving was not a choice for them. Some fled with nothing,” she added.

She added that any response to survivors and their needs arising from conflict-related sexual violence must prioritise their dignity and respect.

Both Nuria and Nadia stress that survivors are not only looking for immediate protection, but also for accountability through “impartial investigations, prosecution of perpetrators, and an end to impunity,” says Nadia. “This is a very important point that we need to have in mind when talking about any violations, not only sexual violence.”

“Survivors are looking for justice and accountability first. Without that, there can be no protection, no dignity, and no peace.”